Before engaging external expertise, a crucial but often overlooked step is a rigorous self-assessment of the business’s internal capabilities in relation to its strategic objectives and operational needs. This diagnostic phase is not merely procedural—it is the foundation upon which effective consultancy is built. For small to medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), where resources are limited and strategic focus is essential, accurately identifying functional or strategic gaps is not optional; it is a necessity. This introspection goes beyond addressing visible symptoms, such as operational hiccups or market pressures, and delves into underlying root causes and systemic weaknesses. It is through this nuanced understanding that the need for external expertise becomes clear, and the potential return on investment (ROI) can be most effectively projected (Kaplan & Norton, 1996; Porter, 1985).

Leveraging SWOT for Gap Analysis

A widely recognized framework for internal assessment is the SWOT analysis—examining Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Threats (Pickton & Wright, 1998). While traditionally used for broad strategic planning, applying SWOT to identify operational or functional gaps requires a sharp focus on internal capabilities.

- Weaknesses: This is more than listing shortcomings. It demands a critical evaluation of skill sets, technology infrastructure, process efficiency, and resource allocation against market demands and growth objectives. For example, a manufacturing SME might recognize a weakness in supply chain management. A deeper analysis would explore whether the problem stems from limited logistics expertise, outdated ERP systems, or insufficient capital for technology upgrades. A service business noticing poor digital marketing results must determine if the root cause lies in SEO and content strategy deficiencies, underutilized social media, or ineffective customer segmentation. This level of analysis converts general weaknesses into actionable gaps that external consultants can directly address (Ginter, Duncan, & Swayne, 2018).

- Opportunities and Threats: Mapping internal weaknesses against external possibilities ensures prioritization of interventions that maximize strategic impact. For instance, limited e-commerce capabilities might be a threat if competitors are excelling in this domain, but also an opportunity if the market is trending online (Kotler & Keller, 2022). This alignment ensures consultancy efforts focus on areas with the highest potential for measurable results, rather than dispersing resources across minor issues.

Complementing SWOT with the Balanced Scorecard

While SWOT provides qualitative insight, the Balanced Scorecard (BSC) offers a quantitative lens. Developed by Kaplan and Norton (1996), BSC evaluates four interconnected perspectives: Financial, Customer, Internal Processes, and Learning & Growth. When adapted for gap identification:

- Financial Perspective: Examine not only profitability but whether internal financial processes, forecasting, or capital allocation are hindering efficiency or growth. Identify opportunities where specialized financial expertise can optimize cost structures or revenue streams (Kaplan & Norton, 2004).

- Customer Perspective: Assess how internal capabilities affect customer satisfaction, retention, and market responsiveness. For instance, declining customer satisfaction may stem from inefficient service processes, slow product development, or inadequate CRM systems (Peppers & Rogers, 2016).

- Internal Processes Perspective: Scrutinize operational workflows—production, sales, marketing, and service delivery. Identify bottlenecks, redundancies, or outdated practices that limit efficiency or quality. Gaps in IT systems or agile methodology adoption, for example, indicate clear areas for consultant intervention (Hammer & Stanton, 1999).

- Learning & Growth Perspective: Focus on the organization’s capacity for innovation and adaptation. Evaluate workforce skills, training programs, information systems, and the culture of continuous improvement. A gap in digital literacy or innovation capability signals the need for targeted training, recruitment, or external guidance (Garvin, Edmondson, & Gino, 2008).

Applying BSC systematically produces a detailed map of internal capabilities versus strategic requirements, moving assessments from subjective impressions to data-driven insights. For example, a decline in customer retention (Customer) combined with supply chain inefficiencies (Internal Processes) and limited logistics expertise (Learning & Growth) highlights a specific, actionable set of gaps that can be addressed strategically.

Tailoring Diagnostic Frameworks

Selecting the right diagnostic framework depends on the nature of the business and the type of gaps. Strategic deficiencies may require qualitative analysis supplemented by competitive benchmarking and customer surveys. Operational issues benefit from workflow analysis, technology audits, and resource evaluation. Tools such as process mapping, performance analytics, and behavioral assessments can further clarify the reasons behind underperformance (Slack, Brandon-Jones, & Burgess, 2022).

Identifying gaps is iterative, not static. Businesses must regularly revisit assessments in response to market changes, technological developments, or internal performance reviews to ensure continued alignment between internal capabilities and strategic goals.

Objectivity and the Role of External Perspective

Intellectual honesty and objectivity are essential. Internal teams may overlook issues due to proximity or organizational politics. An initial, high-level consultation with external experts can provide unbiased insights and guide the diagnostic process. This ensures that consultancy is precisely targeted, addressing root causes rather than superficial symptoms (Greiner & Metzger, 1983).

Constructing a Business Case for Consulting

The decision to engage external consultants must balance strategic necessity with financial prudence. Viewing consultancy as a cost center rather than a strategic investment undermines effectiveness. A robust business case should:

- Project financial gains—revenue increases, cost reductions, efficiency improvements, or risk mitigation.

- Define Key Performance Indicators (KPIs)—specific, measurable metrics directly tied to the consultant’s objectives. Examples include cost reductions, increased throughput, faster deployment cycles, improved customer acquisition, or revenue growth.

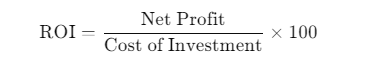

- Quantify ROI to validate investment. ROI is calculated as:

For example, if a $50,000 consultancy yields $200,000 in incremental profits, the ROI is 300%.

Considering Long-Term Value with NPV

Some consulting benefits materialize over time. Net Present Value (NPV) accounts for the time value of money, discounting future cash flows to determine the true value of the investment. For instance, if a $75,000 consultancy generates $100,000 annually in savings over five years at a 10% discount rate, NPV quantifies the profitability more accurately than simple ROI, ensuring informed investment decisions (Brealey, Myers, & Allen, 2020).

Conclusion

Identifying core business gaps and constructing a compelling case for consultancy are critical to maximizing the value of external expertise. By combining SWOT, BSC, and rigorous financial analysis, businesses can pinpoint deficiencies, prioritize interventions, and measure outcomes. This disciplined approach ensures consultancy engagements deliver measurable results, drive sustainable growth, and transform abstract needs into concrete, actionable strategies.

References

- Brealey, R. A., Myers, S. C., & Allen, F. (2020). Principles of Corporate Finance. McGraw-Hill Education.

- Garvin, D. A., Edmondson, A. C., & Gino, F. (2008). Is Yours a Learning Organization? Harvard Business Review.

- Ginter, P. M., Duncan, W. J., & Swayne, L. E. (2018). Strategic Management of Health Care Organizations. Wiley.

- Greiner, L. E., & Metzger, R. O. (1983). Consulting to Management. Harvard Business School Press.

- Hammer, M., & Stanton, S. (1999). How Process Enterprises Really Work. Harvard Business Review.

- Kaplan, R. S., & Norton, D. P. (1996). The Balanced Scorecard: Translating Strategy into Action. Harvard Business School Press.

- Kaplan, R. S., & Norton, D. P. (2004). Strategy Maps: Converting Intangible Assets into Tangible Outcomes. Harvard Business School Press.

- Kotler, P., & Keller, K. L. (2022). Marketing Management. Pearson.

- Peppers, D., & Rogers, M. (2016). Managing Customer Experience and Relationships. Wiley.

- Pickton, D., & Wright, S. (1998). What’s SWOT in Strategic Analysis? Strategic Change, 7(2), 101–109.

- Porter, M. E. (1985). Competitive Advantage: Creating and Sustaining Superior Performance. Free Press.

- Slack, N., Brandon-Jones, A., & Burgess, N. (2022). Operations Management. Pearson.